Section 4. The More Difficult Math – Projecting Out Simply

So, what are the shortcomings here?

It was funny – I thought I had it wired. Then, I plugged this into my budget and…. Whoa things look different down the road. The problem with what I posed above is that it provides you the minimum, but only as of today. But the real risk is what happens tomorrow.

There is a large value in at least knowing where you are today. But if you’re so inclined, I’ll suggest that you think forward “POSitively” – Project Out Simply your budget.

You’ll need a spreadsheet something like this (ok, a LOT like this):

- Put your current expenses into a column. Don’t get too detailed – just put in the “big ones” separately like your house, auto, groceries, doctor bills, and ostrich feed. It’d be good to put Fixed separately from Flexible. Also, if you have a specific future need (say a new car), adding that into a given year can be helpful.

- Set an inflation assumption. Long-Term inflation is generally tame in this country. For the examples, I’ve assumed 3%. So, each of your expenses goes up by taking last year, multiplying by 1.03 and carrying that to the next year.

- Put your income in a column. For Social Security, project out with the same inflation (the government will be close enough to this number).

- Do the Math: Calculate your Income Needed, Your Total Withdrawal (i.e., including taxes) and ratios for each year as in Appendix 1.

- Start with your current Invested Assets as of January 1 of this year.

- Multiply your Invested Assets by a Targeted Investment Rate x (1 – FITRate). This is After-Tax Interest Earned.

- The invested assets next year are the Invested Assets plus After-Tax Interest Earned less the Withdrawal you plan on taking.

- Based on these numbers, you can now calculate your “Minimum Rate Needed” and your “Minimum Assets Needed”. These can be compared to the target rate and the invested assets you generate.

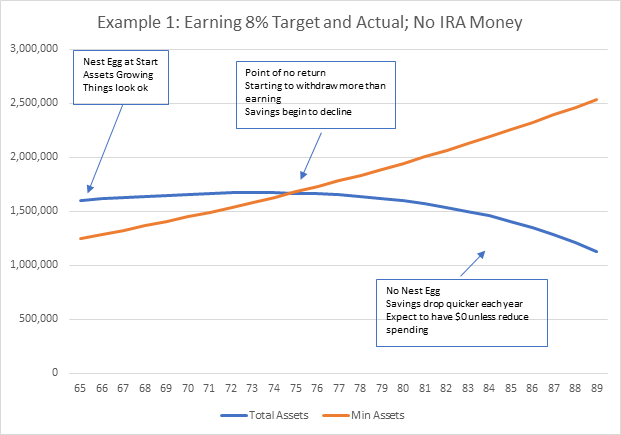

I did Examples (See Appendix 2) to show you what happens with both Pre- and After-Tax money if you project forward, and if all assumptions worked out. For the After-Tax case, I provided this graph:

Wait a minute – I went broke? How’d That Happen?

In the example, the following was seen:

- So, you did the math, and I said that you needed at least $1.25M to retire. And 8% was my target, and I made it!

- I provided 100% of Fixed Income Ratio: Being in Case 2A at retirement.

- You had $250,000 in a “nest egg” (difference of Blue to Orange Line).

- For the first 5/6 years, things look even better. Your $1.6M actually grew just a bit. Starting about age 72, though, your savings started to decline just a bit. But again, that’s ok, right?

- Once you get into your 80’s, everything seems SO expensive. You’re withdrawing even more, and you realize you’ll have to cut out those trips to the Bahamas (unless you take your ostrich as a support animal to reduce costs. After all, they’re not flying there by themselves!)

Now, what’s the math behind this – Your Nest Egg is not only a cushion for today, but the earnings on it are paying for inflation tomorrow:

- Your assets grow by “Net Savings” – The amount you withdraw vs. the amount you earn.

- Minimum Earnings and Asset assumptions are based on you having enough in that year.

- So, if you had the Minimum $1.25M in that year, and you spent and earned exactly the budget, you’d have $1.25M at the end of the year.

- But… Next year the cost of living just increased 3% from $75,000 to 77,250. Now your assets have to pay not only the base expenses but also the increase in expenses due to inflation. That means you’ll have to earn higher than 8% to cover the extra $2,250 in costs.

- That your earnings are taxed, but your expenses are not means that you’ll only have more to pay for.

This is what is meant by “outliving your money” – you never see it coming until it is too late. So, my rule of thumb is this: Don’t Be Like Your Ostriches and bury your head in the sand – Better to fix it now than wait for later. If you measure things and see that you’re not making enough, course-correct your spending earlier rather than hope you won’t have to do it later. Because, by the time your 88, the cost cutting that you’d have to do to make up $148K is unrealistic.

I focus on the negative here (occupational hazard) – remember that the opposite can happen. If you do better than you expect (which we should plan for) then you’ll have the flexibility to take the kids on that cruise (or your ostriches if you think they’re better-behaved company).

Can I fix this problem?

Not really. The math gets too hard and unpredictable. There are a few things worth considering:

1) Try plugging in different “invested assets” amounts to see what the starting value would need to be to carry you out without going bankrupt.

2) I tried this and it sort-of works. If you resolve for your Minimum Total Assets by reducing the target rate by inflation, the number would grow. I’ll call this the “Minimum Inflation Assets”, which is somewhat erroneous terminology but the best I can do. I’ve found that when I do this it is reasonably conservative and projects out an amount that lasts (and sometimes outlasts) my lifetime.

Leave a comment